Healthcare and social services fraud has dominated recent headlines across multiple states and programs. In January 2026, California Attorney General Rob Bonta announced arrests of seven individuals in Monterey County for hospice fraud totaling $3.2 million, part of a broader pattern affecting Los Angeles County where federal officials estimate fraud reaches $3.5 billion. Meanwhile, Minnesota has grappled with its own massive fraud scandal in childcare programs, with allegations of systematic exploitation of publicly funded services.

These cases share a common thread: large-scale fraud in programs serving vulnerable populations, funded by taxpayer dollars, operating with insufficient oversight to prevent bad actors from exploiting the systems.

The political irony is striking. Much of the current attention to these fraud cases comes from political leaders who have historically championed deregulation and opposed government oversight of private markets. Certificate of Need (CON) programs, which require healthcare providers to demonstrate community need before receiving approval to operate, have faced particular scrutiny from those favoring free-market approaches to healthcare. Several states have repealed or scaled back CON requirements in recent years, often with support from those now calling attention to fraud that such regulations might have prevented or minimized.

In light of the continued calls by some for deregulation, California's hospice crisis offers a compelling case study of what happens when healthcare markets lack the structured oversight that CON provides.

Certificate of Need regulations require prospective healthcare providers to prove actual community need exists before they can develop a new healthcare service or facility. Applicants must demonstrate through data and analysis that their proposed services will meet genuine demand without creating wasteful oversaturation. The process includes financial review, public comment periods, clinical and utilization metrics analysis, and sometimes even site visits.

Multiple states maintain CON specifically for services like hospice and nursing homes, recognizing these sectors' vulnerability to fraud and quality issues. California is not unfamiliar with Certificate of Need regulations. The state adopted CON requirements in the 1970s following federal mandate but repealed the program in 1987 leaving the state without these protections for over 40 years. The question now confronting policymakers is whether different regulatory approaches could have prevented the crisis that has unfolded in the nation's most populous state.

The Impossible Math of Oversaturation

Before examining the numbers demonstrating the depth of fraud, it's important to understand why easy market entry for unneeded healthcare providers invites fraud, particularly for a service like hospice.

Unlike hospitals or surgery centers, hospice agencies don't require millions of dollars in capital investment. They typically need only modest leased office space for recordkeeping, since care is delivered in patients' homes. However, this low barrier to entry masks a fundamental economic reality: clinical staff represent both the primary expense and the essential means of generating revenue. Nurses, aides, therapists, and social workers must actually visit patients and deliver care for the hospice to legitimately earn Medicare's per-diem reimbursement.

Healthcare workforce shortages have driven salaries to record highs, particularly in oversaturated markets like LA County where hundreds of duplicative hospice agencies compete for limited qualified personnel. Providers must offer competitive wages to attract and retain staff capable of delivering the required care. Covering those labor costs requires serving hundreds of patients annually – which becomes financially impossible when too many providers compete for a limited pool of hospice-appropriate patients, leaving insufficient volume per provider to sustain operations.

In such oversaturated markets, the only way to generate sufficient revenue is through fraudulent billing for services never rendered or for patients inappropriately enrolled. This is precisely why fraudulent operators flooded California's hospice market: they were created specifically to exploit billing systems, not to provide legitimate care. The numbers in Los Angeles County tell exactly this story of systematic dysfunction rather than organic market growth. With a 2024 population of over 9.7 million, LA County's 1,923 hospice providers represent extraordinary oversaturation that no legitimate market conditions could explain or support.

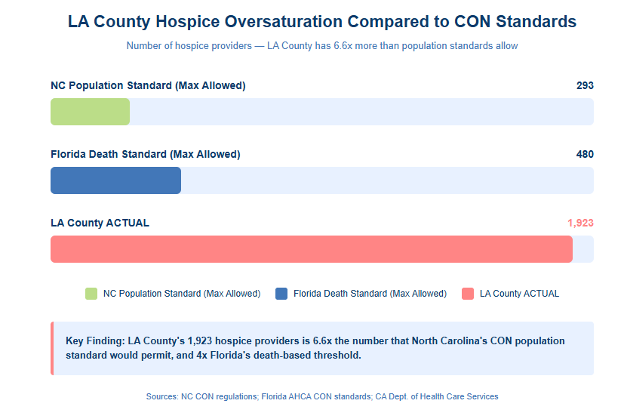

As a contrast, North Carolina's CON regulations limit hospice providers to a maximum of three per 100,000 population, a standard that would allow LA County just 293 hospices. Instead, the county has 6.6 times that number.

The oversaturation becomes even clearer when examining actual patient need rather than just population figures. LA County recorded 336,408 deaths in 2025. Assuming a 50% hospice utilization rate, approximately 168,204 deaths would be appropriate for hospice care. With 1,923 providers competing for these patients, each provider averages just 87.5 deaths annually. This falls far below Florida's CON threshold of 350 deaths needed to demonstrate provider viability.

The statewide picture confirms that this problem extends well beyond Los Angeles County. California's 2024 population of 39,431,263 and approximately 6,000 hospice providers statewide reveal systematic oversaturation. Using North Carolina's standard, California should have a maximum of 1,183 hospice providers. Instead, it has roughly 5 times that number.

California recorded 1,397,006 deaths in 2025, meaning the state's hospice providers average approximately 233 deaths annually each. While this exceeds LA County's dismal average, it still falls well short of the 350-death viability threshold that Florida's CON program uses to ensure providers can operate sustainably while serving genuine need.

These aren't the numbers of a functioning market meeting legitimate demand. They're the numbers of a market that has enabled fraud to flourish at industrial scale.

How We Got Here: Licensing Without Limits

California did have licensing requirements for hospice providers, but licensing and CON serve fundamentally different purposes. Licensing asks whether you meet minimum qualifications: Do you have appropriate credentials? Have you drafted by-laws? Do you have a physical office location? Can you afford the minimal $3,000 filing fee?

CON asks an entirely different question: Is there an actual patient-driven need for your services? The distinction proved critical in California's case.

Anyone who could pass basic licensing requirements could enter California's hospice market regardless of whether any genuine need existed for additional providers. No requirement existed to demonstrate actual community need, no analysis examined whether existing providers already met market demand, and no mechanism prevented unlimited new entrants from flooding already-saturated markets.

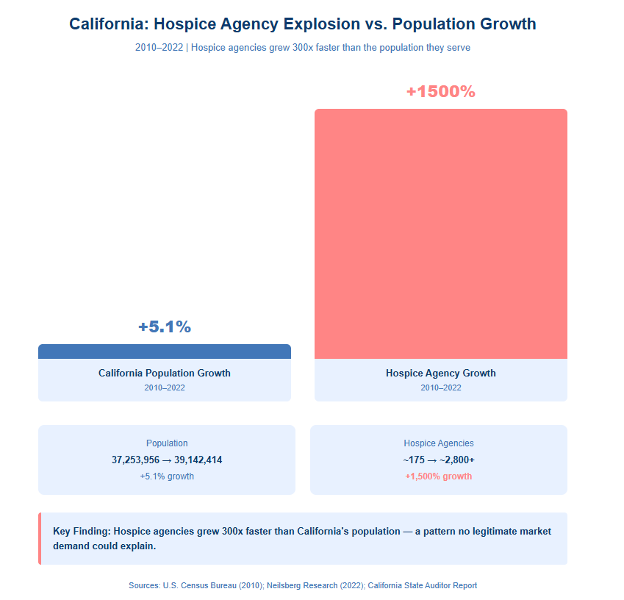

The result was predictable: explosive, unsustainable growth that bore no relationship to the population being served. Los Angeles County experienced a seven-fold increase in hospice billing activity in just five years. The number of hospice agencies grew 1,500% since 2010, while California's population grew only 5.1% during roughly the same period.

State regulators found themselves overwhelmed, unable to meaningfully monitor 1,923 providers in a single county. Federal regulators fared no better, as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) simply cannot provide effective oversight when California alone accounts for such massive provider volume, particularly when approximately 18% of the nation's overall home health and hospice Medicare billing activity occurs in Los Angeles County.

The Fraud Mechanics: What Actually Happened

The oversaturation didn't merely create inefficiency or redundancy. It created the conditions for systematic fraud on a scale that shocked even experienced investigators.

According to California Department of Justice investigations and the California State Auditor, fraudulent operators engaged in patient trafficking, moving patients between shell companies every six months to avoid detection while continuing to bill for services. They recruited and certified patients who didn't suffer from terminal diagnoses, the fundamental requirement for hospice eligibility. Many enrolled patients didn't know hospice was intended for the terminally ill or that they were even enrolled in these programs. Operators submitted claims for services never provided or provided to patients who didn't exist.

The vulnerability of the elderly population made them easy targets for these schemes. When corrupt physicians pressured patients facing health issues to enroll in hospice, those patients lacked the expertise to recognize the fraud. Their Medicare numbers became commodities, described by one industry expert as "more lucrative than credit cards."

The California State Auditor's investigation identified one Los Angeles building supposedly housing more than 150 licensed hospice and home health agencies, a number that exceeded the structure's physical capacity of 22,500 square feet. Another investigation found 42 hospice agencies within a four-block radius in Van Nuys. These weren't legitimate businesses competing for patients; they were shell companies apparently created solely for fraudulent billing.

Critical Red Flags the CON Process Would Have Caught

CON applications require detailed operational projections that serve as fraud prevention and detection tools, creating accountability through specific metrics that reviewers can evaluate for reasonableness and consistency with legitimate operations. Several metrics would have raised immediate red flags about California's hospice market, particularly in Los Angeles County.

Legitimate hospice operations discharge 85-90% of patients due to death, with alive discharge rates of 10-15% being acceptable given the inherent difficulty in predicting end-of-life timelines, particularly for patients with conditions like dementia. Hospice agencies in Los Angeles County had a 26% alive discharge rate in 2019, nearly double the acceptable threshold. This strongly suggests providers were enrolling patients who weren't truly terminal. CON reviewers examining applications with such projections would demand explanation and likely deny approval absent compelling justification.

The California State Auditor also found "unusually long durations of hospice services" in LA County, indicating many patients remained enrolled far longer than clinical appropriateness would suggest. Typical hospice average length of stay (ALOS) ranges from 60 to 90 days nationally, with North Carolina averaging approximately 80 days. Applicants projecting significantly extended stays would face scrutiny about whether they planned to serve appropriate patients or intended to keep non-terminal patients enrolled indefinitely to maximize billing.

Florida's CON standard requires demonstrating need for 350 additional deaths before approving a new hospice provider. With LA County providers averaging just 87.5 deaths annually, the market clearly cannot support existing supply, much less additional entrants. CON applications proposing to enter such saturated markets would be denied for lack of demonstrated need.

The California State Auditor identified geographic clustering that defies any legitimate business explanation, with one building housing over 150 supposed agencies and concentrated areas showing impossible densities of providers. CON's public review process would likely expose such suspicious clustering before licenses were granted, as experienced reviewers and existing legitimate providers would immediately recognize these patterns as indicators of fraud rather than genuine service delivery, and the CON process itself allows those with such knowledge to comment on the proposed service to bring these issues to the regulators.

California's Response: Implementing CON After the Fact

Faced with crisis-level fraud, California took decisive action by implementing the very tools that CON programs have used for decades. In 2021, Governor Newsom signed legislation imposing a moratorium on new hospice licenses, essentially freezing market entry while regulators assessed the damage. The state has since revoked more than 280 licenses and identified approximately 300 additional hospices suspected of malfeasance currently under review.

California didn't stop with enforcement alone. Recognizing that licensing without safeguards against oversupply proved insufficient, the state is now developing regulations that include "geographic service area and unmet need requirements," precisely the type of need-based planning that defines CON programs. Essentially, these are CON standards, implemented reactively after billions in fraud rather than proactively to prevent it.

The California State Auditor's 2022 report documented that as early as 2019, Los Angeles County exhibited multiple fraud indicators including excessive clustering, abnormal discharge rates, and impossible patient volumes. These warnings predated the current crisis by years. Had CON-type oversight been in place, regulators would have been examining and likely rejecting hundreds of suspect applications before they ever opened their doors, rather than scrambling to shut down fraudulent operations after the damage was done.

The National Lesson: Five Ways CON Can Prevent Fraud

While CON programs cannot prevent all fraud, as determined criminals will always attempt to circumvent regulations, it creates meaningful barriers that would have prevented the scale of California's crisis through five protective mechanisms working in concert.

1) Need-Based Guardrails Against Excessive Supply: CON limits providers to demonstrated community need using state-verified data and planning methodologies. Applicants cannot simply assert demand exists; they must prove it using statistics that often include population demographics and growth projections, existing provider capacity and utilization rates, death rates and disease prevalence data, and service area analysis.

When regulators can document that 293 providers adequately serve a population's hospice needs, applications numbered 294 through 1,923 would be denied not because regulators are restricting competition, but because no legitimate need exists.

2) Multi-Layered Front-End Scrutiny: CON applications require extensive documentation that creates multiple checkpoints. Financial analysis demands detailed pro forma projections, capital requirements, and proof of financial backing. Prospective providers often abandon CON efforts when they learn the level of business planning and financial analysis required, functioning as an effective deterrent to fly-by-night operators.

In some states, character and fitness review requires disclosure of criminal history, regulatory violations, and prior healthcare licenses. While applicants might attempt to conceal such information, discovery of undisclosed issues can result in CON and license revocation. Operational planning demands detailed projections of patient volumes, staffing, service delivery, and clinical metrics that create accountability benchmarks.

3) Public Transparency and Review: CON applications are public documents subject to community comment and competitor challenges. This transparency allows existing legitimate providers to identify and challenge suspicious applications, enables community members to raise concerns about proposed operators, creates additional scrutiny through public hearings, and deters bad actors who prefer operating in shadows. The public process allows those most familiar with local markets to inform regulatory decisions and prevent absurd outcomes like LA County's situation.

4) Experienced Regulatory Review vs. Vulnerable Patients: The California fraud schemes succeeded partly by deceiving elderly patients through corrupt physicians. An 80-year-old facing serious health issues lacks expertise to recognize they're being enrolled in inappropriate hospice care.

Experienced CON reviewers examining applications aren't so easily deceived. They are much better positioned, given their experience, to understand hospice metrics, recognize statistical anomalies, and are more likely to identify applications that don't align with legitimate operations. The asymmetry of knowledge reverses: instead of fraudsters exploiting vulnerable patients, experts evaluate fraudsters' proposals with skepticism.

5) Manageable Regulatory Capacity: Perhaps most critically, CON keeps provider numbers within what regulatory agencies can actually monitor and enforce against. California's regulators cannot meaningfully oversee 1,923 hospice providers in one county. But they could effectively monitor 293. Federal regulators face the same capacity constraints, as CMS cannot provide robust oversight when California alone accounts for thousands of providers. CON prevents the problem from occurring in the first place by matching supply to both need and regulatory capacity.

The Federal Funding Factor: Why States Need Structured Tools

Hospice care presents a unique regulatory challenge because it's largely Medicare-funded, giving states limited direct fiscal exposure to fraud. That burden falls on federal taxpayers.

States collect fees from hospice licensing but bear little to no financial consequences if fraud occurs. This creates a complicated dynamic for state regulators. In a world of limited resources, state agencies naturally focus on programs directly impacting state budgets, including Medicaid services, state-funded programs, and other areas where waste and fraud directly affect state finances. State regulators must prioritize among competing demands, and programs that don't directly impact state budgets will inevitably receive less attention than those that do.

This is precisely why CON regulations are so valuable for Medicare-funded services. CON creates a structured, rigorous process ensuring states actively evaluate need and prevent oversaturation rather than passively licensing all applicants who meet minimum qualifications. The framework builds in the oversight that might otherwise take a back seat to more pressing state concerns.

Critically, CON prevents problems from occurring in the first place. Federal regulators wouldn't need to monitor 6,000 California hospice providers if CON had limited the state to the 1,183 providers that population-based standards support. Neither state nor federal regulators can effectively oversee such massive oversaturation, but both could manage appropriately sized provider networks that match actual community need.

Beyond Hospice: Self-Referral and Other Applications

While California's hospice crisis provides the most dramatic recent example, CON's fraud-prevention benefits extend to other healthcare services as well. Physician-owned equipment and facilities present particular risks for unwarranted self-referrals. Under certain exceptions, physicians can own advanced imaging equipment such as MRI, CT, and PET scanners or other healthcare facilities and refer patients to their own equipment.

While most physicians practice ethically, CON limits the impact of bad actors by preventing development of equipment and services exceeding community need. Equipment that could only be financially viable through unnecessary referrals simply doesn't get built. The principle remains consistent across different healthcare services: preventing oversaturation eliminates the conditions that make fraud profitable.

The States That Kept Protection

The hospice fraud crisis hasn't affected all states equally. Several states that largely repealed CON regulations made a telling exception: they maintained CON specifically for services with high fraud-risk profiles. Florida maintains CON for hospice and nursing homes despite repealing it for most other services. Ohio continues to regulate nursing homes through CON after broader repeal. South Carolina recently repealed most CON requirements but specifically preserved them for home health and nursing homes.

Why did these states, which are generally hostile to healthcare regulation, keep CON for these particular services? The answer lies in recognizing that certain healthcare sectors face unique vulnerability to fraud and quality issues. These states determined that the regulatory benefits outweighed ideological opposition to supply controls. Their selective preservation of CON for high-risk services suggests an implicit acknowledgment that some healthcare markets require structured oversight to function properly and protect vulnerable populations.

A Note on Politics and Policy

The hospice fraud crisis has unfortunately become entangled in partisan politics. Some suggest that federal attention stems from California's political alignment rather than the severity of the fraud, while others view California's response to federal involvement as defensive posturing.

Rather than political positioning, this analysis has intentionally focused on data, regulatory mechanisms, and policy outcomes. Fraud affecting vulnerable elderly patients and costing taxpayers billions transcends partisan considerations. Both those who generally favor healthcare regulation and those who typically oppose it can agree that systematic fraud harming seniors is unacceptable.

The question of whether Certificate of Need could have prevented this crisis is a policy question with factual answers, not a political one. The data, fraud indicators, and regulatory mechanisms speak for themselves. Whatever one's views on healthcare regulation generally, the California experience offers concrete lessons about what happens when markets lack appropriate oversight tools. The evidence of what happened, why it happened, and what regulatory tools might have prevented it exists independently of political affiliation or general regulatory philosophy.

Conclusion: An Essential Tool, Not a Silver Bullet

Certificate of Need is not a panacea against healthcare fraud. Determined criminals will always attempt to circumvent regulations, and no system eliminates fraud entirely. But CON is an essential tool that prevents the oversaturation enabling fraud to flourish at industrial scale. The difference between 293 hospice providers and 1,923 isn't merely numerical – it's the difference between a manageable, monitorable market and systematic fraud affecting thousands of vulnerable patients.

CON doesn't eliminate competition; it ensures competition occurs among legitimate providers serving real patient need. When there are 1,923 hospices in one county, most of which are fraudulent, patients don't have "choice," they have chaos. The California articles document seniors unable to access legitimate care because fraudsters have captured their Medicare numbers, preventing legitimate providers from serving them. Real competition happens when qualified providers compete on quality, service, and patient outcomes, not when bad actors outnumber good ones six-to-one.

California's hospice crisis demonstrates what happens without these protections: billions in stolen taxpayer funds, patients trafficked between shell companies, elderly individuals deceived into inappropriate care, and legitimate providers struggling to operate in corrupted markets. The measures California is now implementing – need-based planning, geographic service requirements, enhanced oversight – are precisely what CON programs have provided for decades. These tools existed. California simply hadn't adopted them proactively.